There’s no ethical fashion without intersectionality

How Leah Thomas’s Intersectional Environmentalism movement opened our eyes to the lack of inclusion in ethical and sustainable fashion

In June 2020, the same month that Black Lives Matter protests made their way across the globe, sustainable lifestyle brand Patagonia shared a post on their Instagram account from a young Black activist by the name of Leah Thomas (@greengirlleah).

The post had a simple but important message: environmentalism must be intersectional.

Within hours the post went viral.

Thomas’s important message so eloquently highlighted the lack of inclusion in the world of sustainability. It proved that intersectionality must be applied to all industries and movements, including sustainable and ethical fashion, to ensure marginalised communities are included in the conversation—namely because it’s these groups who are disproportionately affected by issues like the climate crisis. Today we look at how we can apply intersectionality to sustainable and ethical fashion, but first, let’s dive into where it all began.

What is Intersectional Environmentalism?

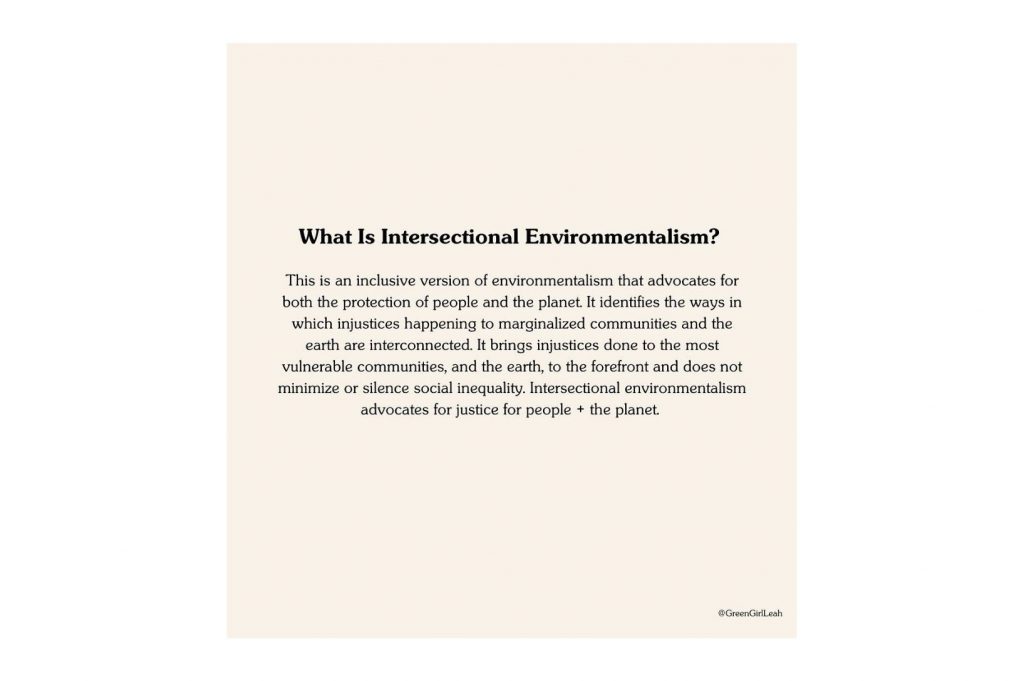

“Environmentalists for Black Lives Matter” were the words that made almost 90,000 Patagonia followers hit the like button and send Leah Thomas’s post into viral territory. The second slide of the Instagram post defined intersectional environmentalism, a movement coined by Thomas that had long been missed from the mainstream sustainability conversation:

“What is Intersectional Environmentalism?

This is an inclusive version of environmentalism that advocates for both the protection of people and the planet. It identifies the ways in which injustices happening to marginalized communities and the earth are interconnected. It brings injustices done to the most vulnerable communities, and the earth, to the forefront and does not minimise or silence social inequality. Intersectional environmentalism advocates for people and the planet.”

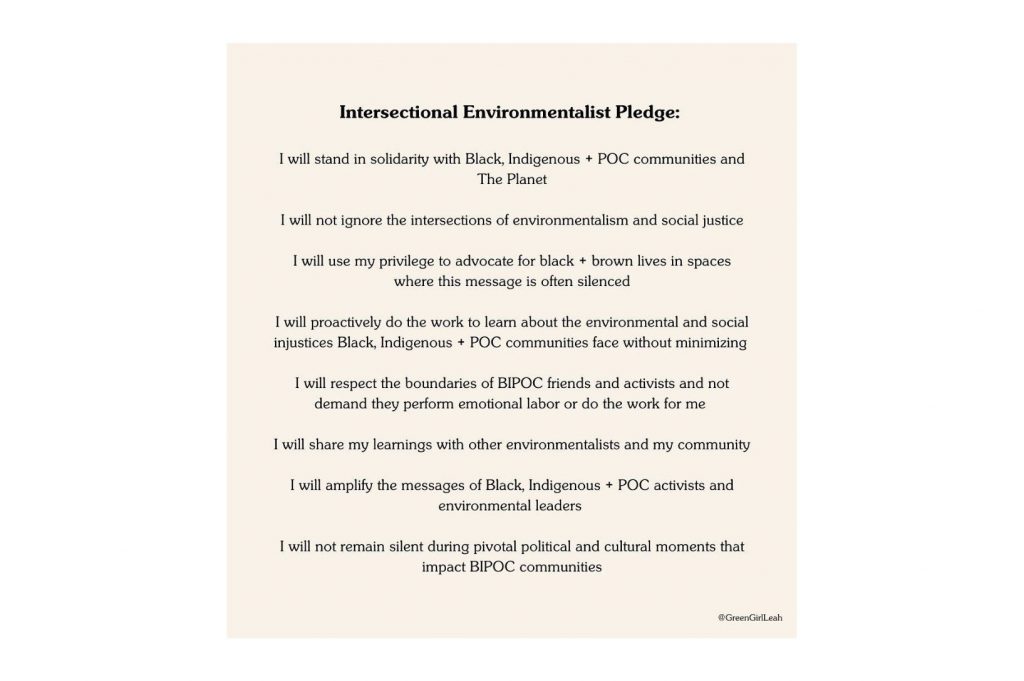

The third slide offered pledges that environmentalists and allies can take to stand in solidarity with Black, Indigenous and People of Colour communities and the planet. Thomas’s message, backdropped by the Black Lives Matter Movement, the rapidly evolving COVID-19 pandemic and the ever-present climate crisis, highlighted the injustices that marginalised communities, particularly BIPOC communities, face each and every day—and even more so during a time of crisis.

Where did the term intersectionality come from?

The first use of “intersectionality” was coined by professor Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989 to describe how race, class and gender intersect with one another. At the time, Mainstream feminism was largely based on the experiences of middle and upper-class heterosexual white women and therefore lacked nuance and diversity.

In response, Black feminists and scholars developed theories to rewrite feminism’s definition, which led to Crenshaw’s popularising of the term “intersectionality”. This Ted Talk by Crenshaw explains how she conceived the term to recognise the prejudice that exists at the intersection of gender and race for Black women.

Leah Thomas and her quest for a intersectionality

Leah Thomas combined Crenshaw’s definition of intersectionality with a topic she’s devoted much of her young life to—environmentalism. But Thomas’s viral moment didn’t come about by chance. In fact, her passion for intersectional environmentalism had been building for years. Prior to going viral and coining a term that was long overdue, she studied environmental science and worked for large sustainability companies including Patagonia, but often felt the BIPOC perspective was left out of the environmentalism narrative.

She explains in an essay for The Good Trade:

“Throughout my studies, I became startled by the facts that it was indeed harder for black, brown, and low-income communities to have access to clean air, water, and natural spaces. Even worse, minority and low-income communities were statistically more likely to live in neighbourhoods exposed to toxic waste, landfills, highways, and other environmental hazards. As my textbooks encouraged me to protect public lands so they could be preserved and enjoyed, I couldn’t help but wonder, “for whom?”.”

Leah further explains in an article for Marie Claire that she felt Black voices were left out of the environmentalism conversation even as she navigated her professional career.

“A study by the Green Diversity Initiative found that only 12 percent of employees and leadership within environmental nonprofits, government environmental agencies, and foundations were people of color. There’s even less representation in government entities—historically, the people who should be influencing and creating equitable environmental policy have been white.” she writes.

As Thomas read about environmental justice from Black activists like Hazel M. Johnson and Dr. Robert J. Bullard, she wondered why those same teachings weren’t offered in her environmental science degree. Leah dared to share her dream for intersectionality through one simple post and finally the collective was beginning to understand the links between environmental issues and race issues. After gaining virality on @patagonia and @greengirlleah, Leah Thomas’s push for intersectional environmentalism was being heard and understood. She took advantage of that viral moment and created a platform called Intersectional Environmentalist (@intersectionalenvironmentalist). Today it has over 360,000 followers on Instagram and Leah has become a spokesperson for the intersectional environmentalist movement.

We must apply intersectionality to ethical and sustainable fashion

In the same way that climate justice cannot be achieved without racial justice, an ethical fashion industry cannot be achieved without recognising BIPOC and minority communities. It’s these groups that are the backbone of the fashion industry but are often underrepresented, left out of the conversation and in worst cases, exploited for profit. Of the 74 million textile workers worldwide, 80% are women of colour—it’s no secret that many of those workers are subjected to poor conditions and criminally low wages.

This article by the Guardian dives deep into how the fast fashion industry is inherently racist, and how this was further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic when companies refused to pay for orders and in turn leaving garment workers in highly vulnerable positions. And don’t even get us started on brands selling t-shirts that read “girl power” when the people who made those same clothes were underpaid BIPOC workers.

There’s also the issue of performative diversity and tokenism. Brands have been called out for hiring Black models to market their clothing while failing to address diversity in their staff. Remake explained in a recent article how, “brands treat diversity as if it is a checkbox on a sheet of paper, rather than a necessary ethical practice and attitude.” If those brands spent the same money on creating more diverse workplaces as they do on performative marketing campaigns, we could actually address intersectionality head on and with the right people leading the way.

Furthermore, the ethical and sustainable fashion industry is one built on privilege. Tired phrases like ‘vote with your wallet’ are only applicable to the select few who can afford it. White influencers take up a majority of the airtime, leaving minority voices out of the conversation.

How do we make sustainable and ethical fashion intersectional?

As the Intersectional Environmentalism website says, “the only way we can tackle this issue is by decolonising fashion and elevating the voices of folks that have been traditionally ignored by the fashion industry, and within the sustainability movement in general.”

Fashion brands cannot call themselves sustainable or ethical without also addressing intersectionality. We need to not only pay textile workers a living wage and ensure their conditions are safe, we must also hold brands accountable for tokenism or lack of diversity, and shift the narrative to amplify BIPOC brands, designers and influencers in the ethical fashion space. Until then, there will be no ethical or sustainable fashion.

If you’re in the market for new clothes, shop with BIPOC led brands. If you’re interested in sustainable fashion, follow a diverse range of voices from BIPOC, disability or LGBTQI communities. Aja Barber and Dominique Drakeford are leading the change in the sustainable fashion conversation.

How can I support intersectional environmentalism?

To support Leah Thomas and her intersectional environmentalism movement, you can take the pledge, donate to IE or join the IE patreon. Also be sure to check out the @intersectionalenvironmentalist Instagram account and learn more about the movement Intersectional Environmentalism Resource Hub.